Glencoe’s Award-Winning History Center

INTRODUCTION[1]

One of the most common questions posed to GHS throughout its Black history research project asks: “Why aren’t there more Blacks in Glencoe today?” Our earliest Black settlers arrived in the mid-1880s at a time when the town’s population was growing steadily. By 1900, Blacks represented 10% of Glencoe’s residents.[2] That growth continued at the same rate through 1920.[3] By 1930, however, the Black population had been reduced by half – to 4.9% of Glencoe’s total population – and has never recovered.[4]

The answer lies in the concerted activities, first of the Glencoe Homes Association (“the Syndicate”) beginning in 1919, and then, the Glencoe Park District, beginning in 1925. Through a combination of actions that applied restrictive racial covenants and eminent domain condemnations to properties in south Glencoe, Black residents were not only driven out of the community, but also effectively prevented from returning. This dark chapter in Glencoe’s history has been consistently overlooked or disregarded in historical compendiums and anniversary celebrations. One of the goals of the GHS Black Heritage Exhibit was to fully research and present the truth about these activities to the community.

[1] This Research Memorandum was written by GHS President Karen Ettelson. Copyright © 2023 Karen Ettelson.

[2] The U.S. Census indicates that out of the 1020 individuals residing in Glencoe in 1900, 102 were Black.

[3] The U.S. Census indicates that out of the 3381 individuals residing in Glencoe in 1920, 329 were Black.

[4] The U.S. Census indicates that out of the 6295 individuals residing in Glencoe in 1930, 313 were Black, demonstrating that the Black population had been reduced to 4.9% of the total. Currently, Black residents represent less than 1% of Glencoe’s total population.

GLENCOE HOMES ASSOCIATION

Although the end result required the work and financial commitment of a number of people, one man had a significant and commanding role in all the activities impacting the Black population. That man was Sherman M. Booth. He “conceived the idea of the Syndicate and as Secretary and Counsel, procured the cash subscriptions and handled the purchase and details of the property and the affairs of the Syndicate generally.”[4] As Booth wrote in numerous affidavits submitted to the Cook County Recorder of Deeds, “I am the Secretary and Counsel of the Glencoe Homes Association, … [and] I have charge and handle all matters relating thereto.”[5]

Although the end result required the work and financial commitment of a number of people, one man had a significant and commanding role in all the activities impacting the Black population. That man was Sherman M. Booth. He “conceived the idea of the Syndicate and as Secretary and Counsel, procured the cash subscriptions and handled the purchase and details of the property and the affairs of the Syndicate generally.”[4] As Booth wrote in numerous affidavits submitted to the Cook County Recorder of Deeds, “I am the Secretary and Counsel of the Glencoe Homes Association, … [and] I have charge and handle all matters relating thereto.”[5]

The Glencoe Homes Association operated through a confidential Land Trust created by Booth. Property purchases were often notarized by Booth,[6] and sales deeds were issued at Booth’s instruction from Booth’s law office.[7] The sales deeds contained severe restrictions on the property, including covenants prohibiting the sale, lease or occupancy, initially by “anyone who is not a Caucasian,”[8] and later, more specifically, stating, “that said premises shall never be sold to, used or occupied by what are commonly known as Negroes, or Italians, or Greeks, or descendants thereof and that if this provision is violated … then the title thereto shall revert to the grantor.”[9]

Despite the fact that the Syndicate’s activities were initially shrouded in secrecy, after the organization had purchased much of the vacant land and homes in south Glencoe, Booth became the public face of the project, meeting with protesting Black residents[10] and reporting on activities to the Glencoe Men’s Club.[11] When progress stalled, Booth shifted the focus of his efforts to the Glencoe Park District where he used his status as a founder of the organization (in 1912), Commissioner (from 1912-1929), President (from at least 1921-1923), Vice President (from 1924-1927), Finance Committee Member (1927) and Improvement Board Member (1927-28) to complete the work begun by the Syndicate. The use of the Park District’s eminent domain condemnation power to create parks along what is now Green Bay Road in the mid-1920s, around South School in the mid-to-late 1920s, and ultimately Monroe Vernon (now Watts) Park in 1928-1930, effectively removed many of the Black and Italian homeowners who had previously refused to sell to the Syndicate.

The impact of Booth’s activities on the Black population in Glencoe was profound. When the GHS exhibit first opened, initial research suggested that the Syndicate had completed 130 transactions involving at least 234 lots in which it purchased and placed restrictive covenants on properties in south Glencoe. Further investigation and examination of records at the Cook County Recorder of Deeds has disclosed significantly more. These records also demonstrate that even after racial restrictive covenants were declared unenforceable by the United States Supreme Court in 1948,[12] these provisions continued to plague Blacks attempting to purchase homes in south Glencoe. As late as 1960, the mortgage lender of a Black purchaser still insisted on a release of the Syndicate’s reverter signed by Sherman M. Booth (as required by the Trust) – even though Booth had died four years earlier.[13]

The impact of Booth’s activities on the Black population in Glencoe was profound. When the GHS exhibit first opened, initial research suggested that the Syndicate had completed 130 transactions involving at least 234 lots in which it purchased and placed restrictive covenants on properties in south Glencoe. Further investigation and examination of records at the Cook County Recorder of Deeds has disclosed significantly more. These records also demonstrate that even after racial restrictive covenants were declared unenforceable by the United States Supreme Court in 1948,[12] these provisions continued to plague Blacks attempting to purchase homes in south Glencoe. As late as 1960, the mortgage lender of a Black purchaser still insisted on a release of the Syndicate’s reverter signed by Sherman M. Booth (as required by the Trust) – even though Booth had died four years earlier.[13]

Research continues. There are too many documents to include all in this memorandum, but the tabs on the left provide more details along with a representative summary and examples of Booth’s activities with the Syndicate and the Park District.

[4] Mann, Clyde A. (National Development Service), Real Estate Investor of Chicago, “First Story of Glencoe Homes Association Best Known to Glencoe as The Syndicate”, December 1927, p. 5 [“REIC”].

[5] Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Letter of Instruction to Jos. F. Haas, Registrar of Titles from Sherman M. Booth, October 29, 1924, Deed No. 235428T.

[6] Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Indenture from Antonio Toscani to Trust #8152, September 2, 1919, Document No. 6611002.

[7] Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Joint Tenancy Deed from Trust #8152 to George and Annie Srnanek, October 1, 1924, Document No. 235123T.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Real Estate Sales Contract from Glencoe Homes Association to George Hogan, September 9, 1925, Document No. 9088712.

[10] “Stop White Agitator in Segregation Plan,” Chicago Defender, June 18, 1921, p. 4.

[11] Glencoe Men’s Club, Minutes of Regular Meeting, October 19, 1921, p. 198.

[12] Shelley v. Kremer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

[13] Cotter, James M. “Mortgage from Peerless Home Builders to Home Federal Savings & Loan Association dated February 9, 1960, Lot 13 in Bloc 5 in Uthe’s Addition to Glencoe.” February 11, 1960 (John H. Burton Papers).

THE SYNDICATE FOUNDERS AND THEIR PURPOSE

The Glencoe Homes Association was established by a land trust agreement dated July 31, 1919, between Chicago Title and Trust Company and seven Glencoe residents: lawyer Sherman M. Booth, banker and transportation executive Markham B. Orde, realtor J. Fred McGuire, Carson Pirie Scott retail executive Bruce MacLeish, lawyer Edwin Cassels, grain dealer Edward L. Glaser and developer Hubert W. Butler. [1] The use of a trust agreement is significant because it was a legal mechanism that protected the privacy and personal liability of the organizers and investors from public disclosure.

The date is peculiar in that it falls squarely in the middle of the Chicago Race Riots which began on July 27, 1919, after “a clash between whites and Negroes on the shore of Lake Michigan at 29th Street … resulted in the drowning of a Negro boy.”[2] The mob action began when a policeman “refused to arrest a white man accused … of stoning the Negro boy.”[3] Thirty-eight persons were killed, 537 were injured and about 1,000 were rendered homeless and destitute as “rioting swept uncontrolled through parts of the city for four days.”[4]

The date is peculiar in that it falls squarely in the middle of the Chicago Race Riots which began on July 27, 1919, after “a clash between whites and Negroes on the shore of Lake Michigan at 29th Street … resulted in the drowning of a Negro boy.”[2] The mob action began when a policeman “refused to arrest a white man accused … of stoning the Negro boy.”[3] Thirty-eight persons were killed, 537 were injured and about 1,000 were rendered homeless and destitute as “rioting swept uncontrolled through parts of the city for four days.”[4]

Amid the riot and its aftermath, at least 25 Glencoe investors paid $1000 for one share each of the Syndicate which was organized to prevent further Black migration from the city and to rid south Glencoe of unsightly buildings and “undesirable” residents.[5] Early investors believed they were performing a “civic duty and protecting their own property, for had they not done so, the Village of Glencoe would have been overwhelmed with the negro colonization and would have ceased to be a desirable residential district for white persons.”[6]

[1] Glencoe Homes Association, Stock Certificate of William A. Baehr, October 11, 1920.

[2] Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago; a study of race relations and a race riot, The University of Chicago Press, (1922).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] REIC at p. 5. “Stop White Agitator in Segregation Plan,” Chicago Defender, June 18, 1921, p. 4.

[6] REIC at p. 5.

HOW THE SYNDICATE FUNCTIONED

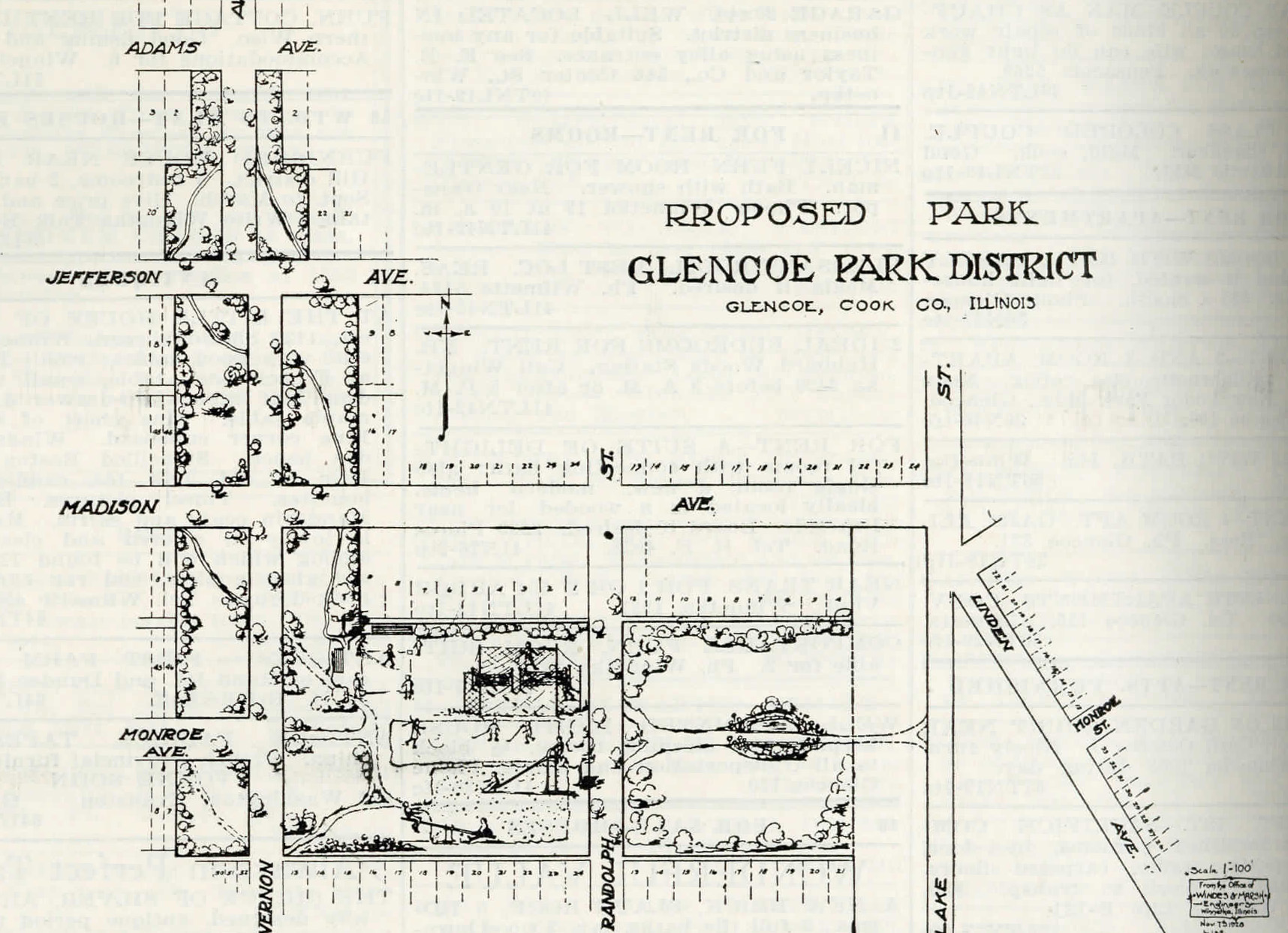

The Syndicate identified land and objectionable structures with the help of a map prepared by Winnetka surveyors Windes and Marsh for Syndicate founder Herbert W. Butler. The map is dated August 14, 1919 (two weeks after the Trust Agreement). The underlying document depicts all the lots in south Glencoe and their owners of record. Structures on lots owned by Blacks were shown by black-filled rectangles. Structures on lots owned by Whites were shown by rectangles filled with diagonal lines. Commercial structures were shown by rectangles filled with crossed lines. In the copy of the map pictured below, the additional colored markings were added by Black Glencoe resident William Rankin, Jr. who used this map to track Syndicate activity.

Because the Syndicate operated under the cloak of a Land Trust (identified in records as CTT #8152), its initial activities were not readily discernable. Most of the Syndicate’s purchases occurred between July 1919 and April 1921. The association employed three different techniques to acquire property. The first was an outright purchase, used primarily when the target was vacant land and the seller was white.[1] In some instances, the group used third party agents who bought property from unsuspecting sellers and then turned around and transferred the property to the Trust.[2]

If the owner of a target (particularly those involving objectionable structures) was unwilling to sell, the Syndicate would offer to help finance repairs with a home improvement-type mortgage. When the owner fell behind on mortgage payments, the Syndicate would acquire the property through foreclosure.[3]

[1] See, e.g., Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Deed from Sale by Hamilton M. Robinson to CTT #8152, July 31, 1919, Tract Index Document No. 6590145.

[2] Compare, Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Deed from Sale by Walter E. Bahls to Ota Perkins, August 20, 1920, Tract Index Document No. 119675T, with Deed from Sale by Ota Perkins to CTT #8152, August 25, 1920, Tract Index Document No. 119676T.

[3] See, e.g., Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Deed from Sale by Firman Turner to CTT #8152, November 19, 1919, Document No. 107229; Mortgage from Firman and Annie Turner, November 6, 1919, Document No. 107228. See also, “Interest in Mortgage Corporation Grows,” The Chicago Whip, November 12, 1921; “To Begin Home Development,” The Chicago Whip, November 26, 1921.

SHERMAN BOOTH’S ROLE IN THE SYNDICATE

Even though much of the work of the Syndicate was hidden behind the confidential terms of the land trust, public documents filed with the Cook County Recorder of Deeds reveal the scope of Sherman Booth’s participation and leadership in the endeavor. He can be found as a Notary on purchase documents. Sales deeds were issued at his instruction from his law office and with the restrictions he specified. Those deeds were accompanied by a letter on Booth’s Law Office letterhead, signed by Booth, stating that he was the “Secretary and Counsel of the Glencoe Homes Association … [and that he had] charge and handle[d] all matters relating thereto.”

Copies of sales contracts and deeds from the Syndicate’s Trust to new purchasers show even greater Booth involvement. A contract dated September 9, 1925, is illustrative. George Hogan purchased Lot 20 in Block 5 of Culver and Johnson’s Addition to Glencoe on September 9, 1925, for $2,125. He paid $250 down and agreed to pay the remaining $1875 within five days at the office of Sherman M. Booth who signed and held the earnest money and the contract for the Syndicate under the terms of the document.[1]

This contract further shows the extent of the restrictive covenants placed on Syndicate purchasers. The lot contained two frame buildings (pictured below) that Hogan agreed to demolish. As part of his purchase, however, he also agreed to construct a single-family home at a cost of not less than $9,000 set back no less than 40 feet from Jefferson Avenue and a private garage only. Most significantly, Hogan agreed, “that said premises shall never be sold to, used or occupied by what are commonly known as Negroes, or Italians or Greeks, or descendants thereof and that if this provision is violated by the grantee or his successor or assigns, then the title thereto shall revert to the grantor or its assigns.”[2]

The restrictive covenants in subsequent Syndicate deeds detailed the racial and ethnic prohibitions with even greater specificity. Purchasers agreed:

“[N]o part of said premises or any improvements of any nature erected thereon shall be sold to, used or occupied by what are commonly known as Negroes, or descendants thereof;

that no part of said premises or any improvements of any nature erected thereon shall be sold to used or occupied by what are commonly known as Italians, or descendants thereof;

that no part of said premises or any improvements of any nature erected thereon shall be sold to, used or occupied by what are commonly known as Greeks or descendants thereof;

that if this provision and restriction is violated by the grantee or successor in title or any of them, then the title to such part of said premises as shall have violated the foregoing provision shall revert to the grantor its assigns …”[3]

Not much is known about the Greek population of Glencoe during this period. The addition of Italians to the list of prohibited groups, however, reflected the growth of their community within the Village.

In March of 1929, Central School Superintendent Arthur B. Rowell spoke to the Glencoe D.A.R. about issues facing “foreign born” individuals living in Glencoe.[4] At that time, the largest group, comprising one-sixth of the population, was Italian, including 127 children under the age of 21. Rowell stated that the Italians fell into two groups: families who were permanent residents and a “floating population of day laborers.”[5] He added, “Physical and moral conditions naturally furnish a problem under these circumstances.” [6] The Syndicate’s solution to the problem was to prohibit the sale, use or occupation of property in south Glencoe by any of these individuals or their descendants.

In March of 1929, Central School Superintendent Arthur B. Rowell spoke to the Glencoe D.A.R. about issues facing “foreign born” individuals living in Glencoe.[4] At that time, the largest group, comprising one-sixth of the population, was Italian, including 127 children under the age of 21. Rowell stated that the Italians fell into two groups: families who were permanent residents and a “floating population of day laborers.”[5] He added, “Physical and moral conditions naturally furnish a problem under these circumstances.” [6] The Syndicate’s solution to the problem was to prohibit the sale, use or occupation of property in south Glencoe by any of these individuals or their descendants.

When the GHS exhibit first opened, initial research suggested that the Syndicate had consummated at least 130 transactions involving at least 234 lots in which it purchased and placed restrictive covenants on properties in south Glencoe. Further investigation and examination of records at the Cook County Recorder of Deeds has disclosed significantly more transactions. A final count is not yet available, but the evidence thus far indicates that the Syndicate successfully placed racially restrictive covenants on hundreds of lots in south Glencoe.

The reverter clause, an essential element of the restrictive covenant, was effective in preventing sales to Blacks, Italians and Greeks at least until the Supreme Court ruled in 1948, that racially restrictive covenants were unenforceable.[7] Nevertheless, these clauses continued to cause problems for Blacks and other prohibited purchasers whose mortgage lenders still insisted on a release of the reverter signed by Sherman M. Booth (and required by the Trust) as late as 1960 – several years after Booth’s death.

As Syndicate holdings increased, Booth became the public face of its activities and efforts. He appeared at a community meeting with Black residents who protested the Syndicate’s efforts and candidly admitted that the Syndicate “did not want any undesirables in the village.”[8] When pressed to define “undesirables,” Booth stated, “[N]o undesirables from the Second Ward of Chicago” undoubtedly aware that most new Black property purchasers were coming from this area.[9] After Morris Lewis, who was the Circulation Director of the Chicago Defender, a resident of the Second Ward of Chicago, and also a Glencoe summer resident objected, Booth countered only by saying that “he did not include Mr. Lewis as an undesirable.”[10]

The Minutes of the Glencoe Men’s Club from October 19, 1921 (more than two years after the Syndicate was formed) similarly show Booth in a leadership role:

“Mr. Sherman Booth gave the first public report of the syndicate formed to purchase property in the south part of Glencoe now tenanted by rather undesirable citizens. His report showed really remarkable strides made by the syndicate and indicated that in a very short time the purpose of the syndicate will be accomplished.”[11]

As more Black residents became aware of Syndicate activity, however, the Black community rallied to resist. In November 1921, a Black mortgage company from the Second Ward gave presentations at meetings along the North Shore to help educate the Black community and offer ways to address the growing concern.[12] When Syndicate efforts stalled, Booth turned to his leadership role in the Glencoe Park District to help finish the job.

[1] Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Contract of Purchase by George Hogan from CTT #8152, September 9, 1925, Document No. 9088712.

[2] Ibid. Emphasis added.

[3] See, e.g., Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Deed from CTT #8152 to John F. and Delphine B. Carney, April 21, 1926, Document No. 299820T. Emphasis added.

[4] “Arthur B. Rowell Gives Talk at Glencoe D.A.R.,” Glencoe News, March 16, 1929.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Shelley v. Kremer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

[8] “Stop White Agitator in Segregation Plan,” Chicago Defender, June 18, 1921, p. 4.

[9] Ibid. See generally, Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago; a study of race relations and a race riot, The University of Chicago Press, (1922), p. 605-613.

[10] “Stop White Agitator in Segregation Plan,” Chicago Defender, June 18, 1921, p. 4.

[11] Glencoe Men’s Club, Minutes of Regular Meeting, October 19, 1921, p. 198.

[12] “Interest in Mortgage Corporation Grows,” The Chicago Whip, November 12, 1921; “To Begin Home Development,” The Chicago Whip, November 26, 1921.

BOOTH’S PARK DISTRICT LEVERAGE

Sherman Booth and his wife, Elizabeth, moved to Glencoe on May 1, 1910, shortly after the birth of their second son. Almost immediately, Booth became involved in the community. He joined the Glencoe Men’s Club, and in 1912, became one of the founding members of the Glencoe Park District.[1]

Sherman Booth and his wife, Elizabeth, moved to Glencoe on May 1, 1910, shortly after the birth of their second son. Almost immediately, Booth became involved in the community. He joined the Glencoe Men’s Club, and in 1912, became one of the founding members of the Glencoe Park District.[1]

In its early years, the Park District functioned primarily as a quasi-zoning organization rather than as a body developing recreational programs and facilities. The Board’s first report stated it had been “organized under a mandate by the public to protect the gate-way to the Village against the encroachment of undesirable and disfiguring business structures and [was] particularly charged with acquiring all vacant property … immediately opposite the station on the north side of Park Avenue.”[2]

It is against this backdrop of property acquisition to remove undesirable elements that Booth’s extensive Park District service must be viewed. He was a Commissioner on the Board continuously for 17 years from 1912 to 1929.[3] He served as President of the Board from at least 1921 through 1923[4] at a time when Syndicate land acquisition in south Glencoe began to slow. He then served as Vice President from 1924 through 1927 when he also was a member of the Board’s Finance Committee.[5]

Booth was a member of the Park District Board of Improvement in 1927 and 1928 at a critical time when plans for the Monroe Vernon (now Watts) Park were being developed. Despite the fact that he officially left the Board in 1929, Booth remained active in the legal proceedings to condemn homes owned by Black and Italian residents in preparation for construction of the Park.[6] Booth’s own correspondence also indicates that he was still consulting with Park Board Commissioners on matters after his departure from the Board.[7]

[1] Glencoe Park District, Report of Commissioners, April 30, 1916, p. 1.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid. See generally, Glencoe Park District, Minutes of Board Meetings, 1923-1930, inclusive

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] See, e.g., Booth, S.M., “Memorandum on Restricted Sales,” dated April 15, 1930 (Glencoe Park District Records).

[7] See, e.g., Booth, S.M., “Letter to Knox Booth,” dated April 12, 1929 (Sherman Booth Papers).

PARK DISTRICT POWER OF EMINENT DOMAIN

Although much of the community today enjoys the features of Watts Park, its history is not widely known. Indeed, when preparing the Master Plan for Parks and Recreation, published in October 1968, before the Village Centennial, Walter Johnson, the Director of Parks and Recreation, omitted a description of Monroe Vernon Park in his historical summary, “reluctantly yielding to pressure from the Glencoe Human Relations’ Board.”[1]

The Park District, however, under the leadership and guidance of Sherman Booth, played a large role in restructuring the physical and demographic appearance of south Glencoe.[2] During its early years, the Park District sought to acquire properties for parks through purchase and donation.[3] That process began to change in the early 1920s. The Park Board, acting on a petition by local residents, condemned the property at 386 Jackson Avenue (owned by Black resident Felicity Gordon) for a small park in July of 1923.[4]

The Board’s focus shifted significantly in July of 1925, with the creation of the Park District Board of Local Improvements.[5]

At the time, the Park Board consisted of five commissioners elected to staggered six-year terms. The Board of Local Improvement functioned basically as a sub-committee of the regular Park Board. It generally had three members (although on occasion was expanded to five), appointed by the Park Board President from the Board’s own ranks.[6] The Board of Local Improvements reviewed and defined projects, estimated costs, and made recommendations in the form of Ordinances for the general Board to consider and pass.

Starting in 1925, this Improvement Board was the impetus for acquisition of land for parks along Green Bay Road and around the new South School.[7] It was also the group, during Sherman Booth’s tenure, that developed the plans for Monroe Vernon Park. That planning likely began in 1927, as evidenced by the fact that the Board approved the payment of additional legal fees for “special matters” in May 1927.[8]

During the summer of 1928, the Improvement Board received petitions from local residents (which may have been started and/or aided by Park District supporters), asking the Board “to institute proceedings to acquire by condemnation” the property needed for Monroe Vernon Park “and improve and pay for by special assessment … spread over a period of twenty years.”[9]